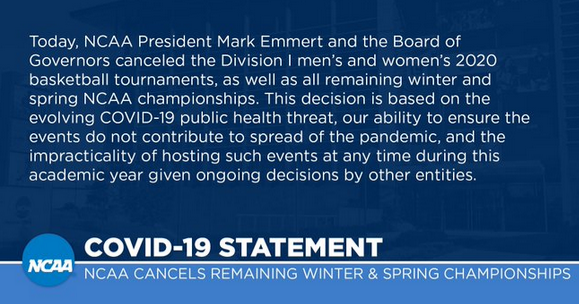

UPDATE, March 12: The tournaments have been canceled>

In a decision that came to be somewhat inevitable, the NCAA on Wednesday announced that due to concerns about the coronavirus, all its championship events, including the men’s and women’s division 1 basketball tournaments, would be held “with only essential staff and limited family attendance,” meaning that regular fans would not be allowed in the venues.

In a decision that came to be somewhat inevitable, the NCAA on Wednesday announced that due to concerns about the coronavirus, all its championship events, including the men’s and women’s division 1 basketball tournaments, would be held “with only essential staff and limited family attendance,” meaning that regular fans would not be allowed in the venues.

Though many sports teams are being dragged grudgingly into such bans, the overwhelming advice from medical experts in the past few days has been that “non-essential” large public gatherings like sports events should be canceled or closed to fans, to help combat the spread of the disease. As reports of new cases of Covid-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, continue to expand, many cities, states and other governing bodies are already taking matters into their own hands and prohibiting any large-crowd events.

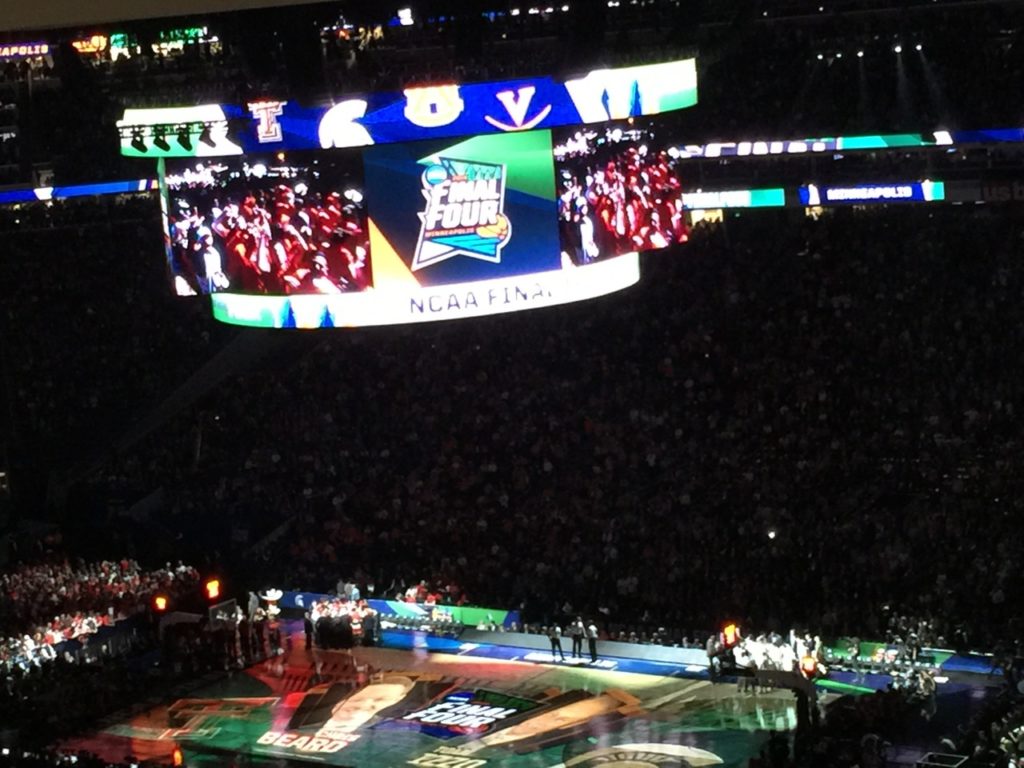

What remains to be seen with other sports, especially professional leagues like the NBA, NHL and Major League Baseball, is whether games will be canceled, moved, or played in place without fans. Also not yet known is whether the NCAA will move its Final Four games from the large arenas where they are scheduled to be played (the men’s Final Four is supposed to take place in Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta, with capacity for more than 70,000 fans) to smaller arenas. In an tweet from an AP reporter, apparently the NCAA is already considering such moves:

Mark Emmert says the NCAA is looking to move the Final Four out of Mercedes-Benz Stadium into a smaller venue in Atlanta.

Regional sites could also be moved from the currently scheduled arenas to smaller venues in same cities.

The plan is to keep sites for the 1st round as is.

— Ralph D. Russo (@ralphDrussoAP) March 11, 2020

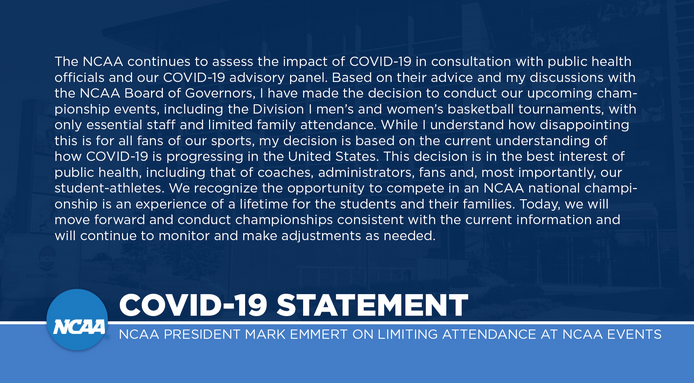

Here’s the full Covid-19 statement from NCAA president Mark Emmert: