A temporary under-seat Wi-Fi network helped bring connectivity to courtside seats at this year’s Final Four. Credit all photos: Paul Kapustka, MSR (click on any picture for a larger image)

One of the traditional characteristics of the Final Four is the yearly travel scramble of the fortunate fans and teams who have advanced to the championship weekend. Somehow, with only a week’s notice, plane flights, road trips and hotel rooms get scheduled and booked, leading to packed houses at college basketball’s biggest event.

On the stadium technology side, a similar last-minute fire drill happens just about every year as well, as the hosting venues reconfigure themselves to host basketball games inside cavernous buildings built mainly to hold football crowds. At this year’s NCAA Men’s Final Four at U.S. Bank Stadium in Minneapolis, the stadium tech team and partner AmpThink were able to quickly construct a temporary Wi-Fi network to cover the additional lower-bowl seating. The new capactity was part of a record-setting Wi-Fi network performance at the venue, with single-day numbers surpassing those from Super Bowl 52, held in the same building the year before.

The Wi-Fi numbers, both staggering and sobering especially to venues who are next in line for such bucket-list events, totaled 31.2 terabytes for the two days of game action, according to figures provided by the NCAA. For the semifinal games on Saturday April 6, U.S. Bank Stadium’s Wi-Fi network saw 17.8 TB of traffic, topping the 16.31 TB used during Super Bowl 52 on Feb. 4, 2018. The Saturday semifinals also set an attendance record for the venue, with 72,711 on hand, topping the 67,612 in attendance for Super Bowl 52.

During the championship game on April 8, U.S. Bank Stadium saw an additional 13.4 TB of data used on the Wi-Fi network, giving the venue three of the top four single-day Wi-Fi numbers we’ve reported, with this year’s mark of 24.05 TB at Super Bowl 53 in Atlanta the only bigger number. Saturday’s take rate at U.S. Bank Stadium, however, surpassed even the most-recent Super Bowl, with 51,227 unique users on the network, a 70 percent take rate.

‘Like building an arena network inside a football stadium’

Editor’s note: This report is from our latest STADIUM TECH REPORT, an in-depth look at successful deployments of stadium technology. Included with this report is a profile of the new Wi-Fi network at Allianz Field in St. Paul, Minn., and an in-depth research report on the new Wi-Fi 6 standard! DOWNLOAD YOUR FREE COPY now!

There’s no doubt that the temporary network installed by AmpThink and the U.S. Bank Stadium IT team contributed a great deal to the final Wi-Fi totals, with 250 access points installed in the additional seats. Like at other football venues that are transformed into basketball arenas, U.S. Bank Stadium had temporary seating installed on all four sides of the stadium, with temporary risers stretching down over football seating as well as with risers built behind both baskets. More seats were installed on the “floor” of the football field, right up to the elevated court set in the middle. The temporary APs, like the existing ones in the stadium, are from Cisco.

“There are a lot more moving parts to a Final Four than to a Super Bowl,” said David Kingsbury, director of IT for U.S. Bank Stadium, describing the difference in providing the networking and technical underpinnings for each event. While planning for the networks was obviously done far in advance, the actual buildout of the temporary Wi-Fi couldn’t even begin until the additional seating was in place, a task that finished just five days before the first game was played.

That’s when AmpThink deployed a staff of 12 workers to start connecting cables to APs and to switches, while also adding in another 700 wired network connections to the courtside areas for media internet and TV monitor connections. Like it does for every venue network it designs and deploys, AmpThink came to the stadium equipped with a wide assortment of lengths of pre-terminated cables, preparation that made the fast deployment possible.

“If we had to spin raw cable and terminate it on site, we never would have been able to finish in five days,” said AmpThink president Bill Anderson.

AmpThink’s previous experience in deploying such temporary networks under temporary seating — including at the previous year’s Final Four in San Antonio — taught the company that it would also need protection for under-seat switch deployments, to fend off the inevitable liquid spills from the seats above. That requirement was potentially even more necessary at U.S. Bank Stadium, since this year’s Final Four was the first to allow in-venue sales of alcoholic beverages.

With some of the temporary seating installed over existing seating, there were 95 APs in the existing handrail-enclosure design that had to be turned off for the Final Four, according to Kingsbury. The 250 new APs added were all installed under the folding chairs, in enclosures that simply sat on the floor.

According to AmpThink’s Anderson, the company did learn a lesson at U.S. Bank Stadium — that it will, at future events, need to secure the actual enclosures since during the weekend curious fans opened a few of the boxes, with one AP disappearing, perhaps as an interesting IT souvenir.

In San Antonio, AmpThink had zip-tied the enclosures to chairs, which led to increased labor to detatch the devices during the post-event breakdown. While having no such measures at U.S. Bank led to a fast removal — AmpThink said it had removed all the temporary network elements just seven hours after the championship game confetti had settled — for next year’s Final Four AmpThink plans to at least zip-tie the enclosures shut so that fans can’t attempt any ad hoc network administration.

More APs for back of house operations

Another difference between the Final Four and the Super Bowl is the fact that four, not two, teams are in attendance for a full weekend, necessitating the need to set up temporary “work rooms” adjacent to each school’s locker room area. The media work center for the Final Four is also typically larger than that of a Super Bowl, again with more cities and their attendant media outlets on site thanks to there being four, not just two, teams involved.

“We had to cover a lot of places in the stadium that we don’t normally cover” with wireless and wired network access, Kingsbury said, saying that an additional 30 APs were needed for team rooms and the main media workspace, which were located on the field level of the stadium in the back hallways. An interesting note at U.S. Bank Stadium was that the yards and yards of fabric used as curtains to cover the clear-plastic roofing and wall areas was actually benefical to Wi-Fi operations, since it cut off some of the reflective interference caused by ETFE surfaces.

According to Kingsbury the final count of active APs for the Final Four was 1,414, a number reached by adding in the temporary APs while deducting the ones taken offline. Not included in the official NCAA traffic numbers was an additional 3 TB of traffic seen during the free-admission Friday practice sessions, when 36,000 fans visited the stadium, with 9,000 joining the Wi-Fi network.

From the official stats, the peak concurrent user number from Final Four Saturday of 31,141 was also an overall record, beating Super Bowl 53’s mark of 30,605. (Super Bowl 53 had 70,081 fans in attendance for the Feb. 3 game between the New England Patriots and the Los Angeles Rams.) The Wi-Fi network numbers for Monday’s championship game (won by Virginia 85-77 over Texas Tech in overtime) saw big numbers itself, with 13.4 TB of total data used, and 48,449 unique connections and 29,487 peak concurrent users (out of 72,062 in attendance). Monday’s game also produced a peak throughput number of 11.2 Gbps just after the game ended.

None of those totals could have been reached without the temporary network, which AmpThink’s Anderson compared to “building a 10,000-seat arena network inside a football stadium.” Next stop for a temporary Wi-Fi network is Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta, where the 2020 Final Four awaits.

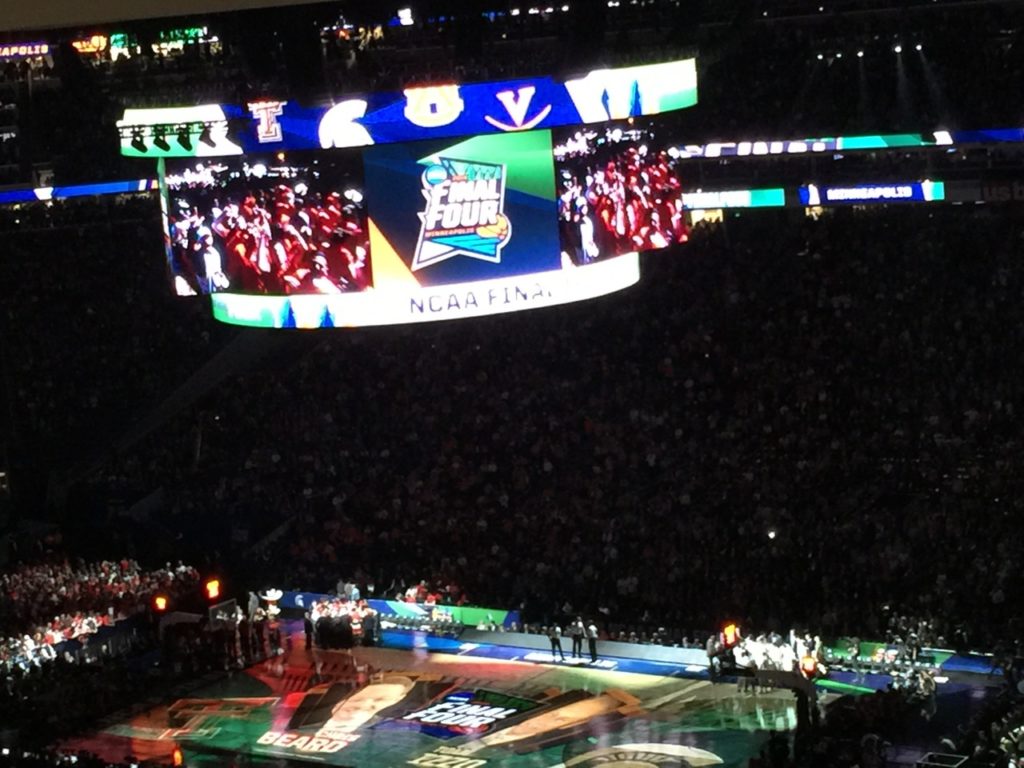

This is what your football stadium looks like with a championship basketball game inside of it.

The temporary center-hung scoreboard was able to play video programming onto the court surface.

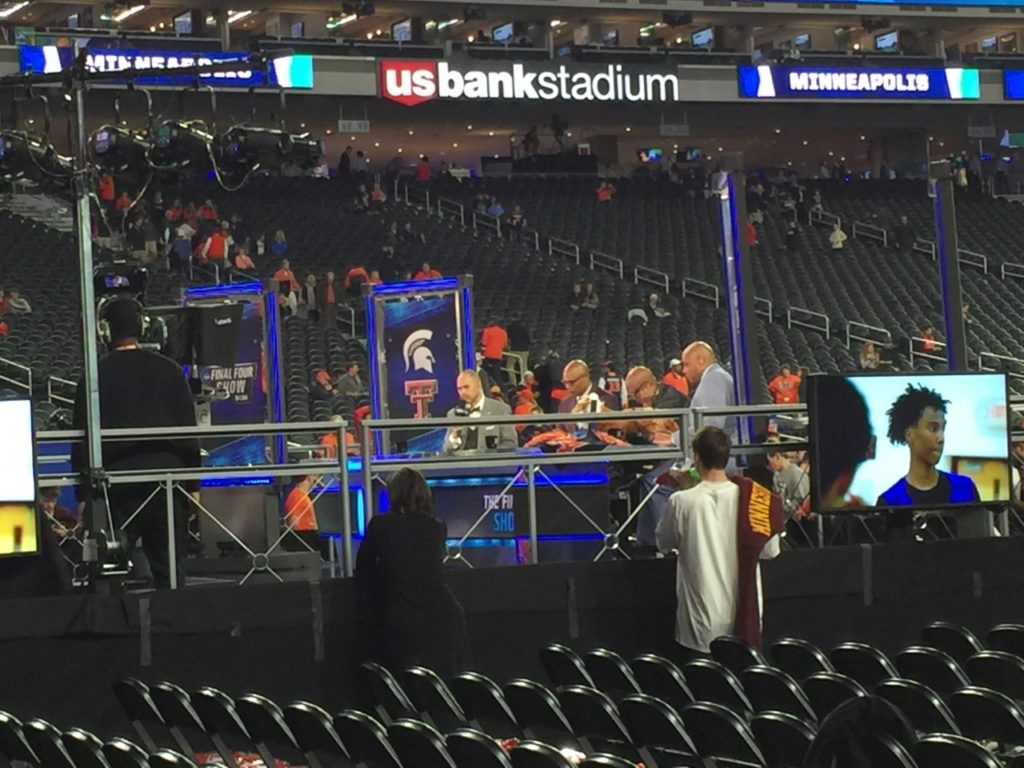

The NBA on TBS crew was courtside for the Final Four.

The secret to keeping your network operations room running? All kinds of energy inputs.