A beer vendor at Wrigley Field this summer. Credit all photos: Paul Kapustka,, MSR (click on any photo for a larger image)

And you don’t need an app to order a frosty malt beverage. You simply say, “Hey! Beer man! One over here!” And he walks over and pours you a cold one. Apparently this is not new, but has worked for many, many years.

Though I do jest a bit I hope my point is clear: Sometimes there is a bit too much fascination with technology, especially on the stadium app front, which has not yet been warranted. The main question of this essay is whether or not it’s time to rethink the in-seat ordering and delivery phenomenon, to find what really matters to fans and where technology can deliver better options.

Who really wants in-seat delivery?

Editor’s note: This profile is an excerpt from our latest STADIUM TECH REPORT, our Fall 2017 issue that has in-depth profiles of network deployments at Notre Dame Stadium, Sports Authority Field at Mile High, Colorado State’s new stadium, and the Atlanta Falcons’ new Mercedes-Benz Stadium. DOWNLOAD YOUR FREE COPY of the report today!

I will be the first to admit to being guilty as charged in being over-excited about stadium apps and the idea of things like instant replays on your phone and being able to have food and drink delivered to any seat in the stadium. When the San Francisco 49ers opened Levi’s Stadium four years ago, those two services were fairly unique in the sporting world, and it was cool to see how both worked.

The Niners did a lot of human-engineering study on the food delivery problem, knowing that it was more an issue of getting enough runners to deliver the goods than it was to get the app working right. Even a big glitch at the first-year outdoor ice hockey game at Levi’s Stadium was sort of a confirmation of the idea: That so many people tried to order food deliveries it screwed up the system wasn’t good, but it did mean that it was something people wanted, right?

Turns out, no so much. Recently the Niners officially announced that they are taking a step back on in-seat concessions ordering and deliveries at Levi’s Stadium, limiting it to club areas only. Whatever reasons the Niners give for scaling down the idea, my guess is that it mainly had to do with the fact that it turns out that the majority of people at a football game (or basketball too) may not want to just sit in their seats the whole game, but in fact get up and move around a bit.

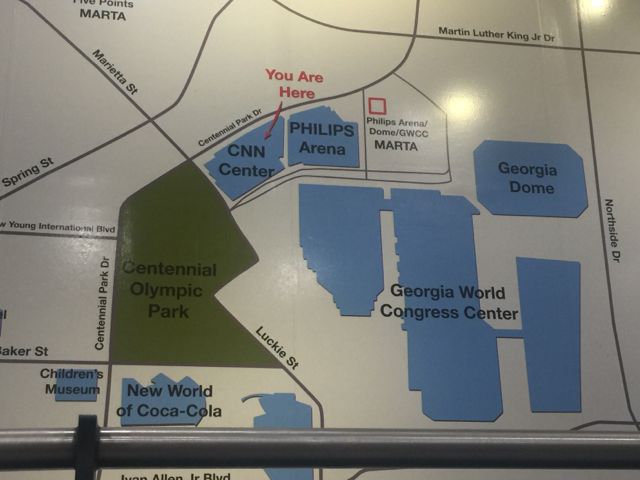

That may be why most of the new stadiums that have opened in the past couple years have purposely built more “porch” areas or other public sections where fans can just hang out, usually with somewhat of a view of the field. The Sacramento Kings’ nice beer garden on the top level of Golden 1 Center and the Atlanta Falcons’ AT&T Perch come to mind here. For the one or two times these fans need to get something to eat, they are OK with getting up and getting it themselves.Plus, there’s the fact that at the three or four or more hours you’re going to be at a football game, if you’re drinking beer you’re going to eventually need to get up anyway due to human plumbing. We’ve been fairly out front in saying stadiums should spend more time bringing concession-stand technology into the 21st century, instead of worrying too much about in-seat delivery. It’s good to see there are some strides in this direction, with better customer-facing interfaces for payment systems and things like vending machines and express-ordering lines for simple orders.

While there may be disagreement about whether or not in-seat delivery is a good idea, there is certainly universal disgust for concession lines that are long for no good reason. It’s beyond time for stadiums to mimic systems already in place at fast-food restaurants or coffee shops and bring some of that technology spending to bear in the place that everyone agrees still needs work. Even at the uber-techno Levi’s, regular concession stand lines have been abysmal in their slowness. Maybe the Niners and others guilty of the same crimes will pay more attention to less flashy fixes in this department.

Is drink-only delivery the right move?

The Niners’ revolutionary attempt to bring mobile ordering and in-seat delivery to all fans in a big stadium was part of the app suite from VenueNext, the company the Niners helped start as part of their Levi’s Stadium plans. While VenueNext is regularly adding new pro teams to its stable of customers (in September at Mobile World Congress Americas, the Utah Jazz announced they would switch to VenueNext for the upcoming season), not a single one has tried to copy the Niners’ ambitious deliver-anywhere feature.

And for Super Bowl 50, the signature event that Levi’s Stadium was in part built for, remember it was the NFL shutting down the idea of in-seat delivery of food and drink, limiting the service instead to just beverage ordering and delivery. It probably makes sense for Mobile Sports Report to put together a list sometime soon about the various attempts at in-seat ordering and delivery around the pro leagues, to see what’s working and what hasn’t. To be clear we are talking here about widespread delivery to all seating areas, and not the wait-staff type delivery systems that have been widely deployed in premium seating areas for years.Our guess, just from tracking this phenomenon the past several years, is that while such services make sense in premium and club areas, simple logistics and stadium real estate (like narrow aisles or packed, sellout crowds) make in-seat ordering and delivery a human-factor nightmare in most venues.

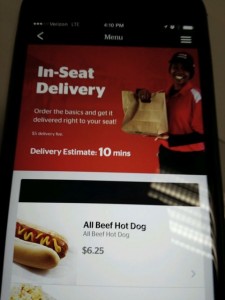

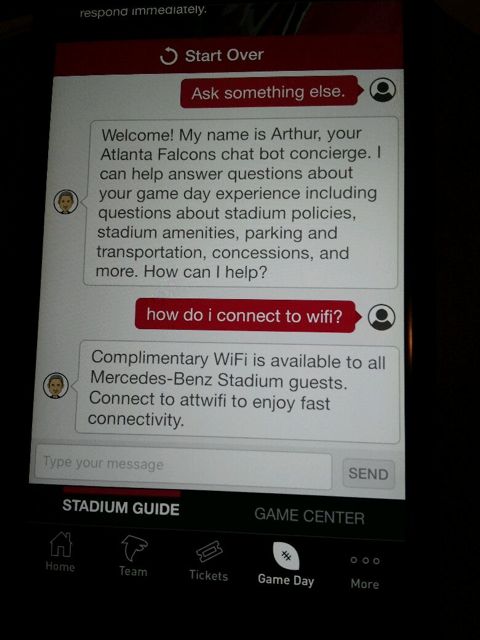

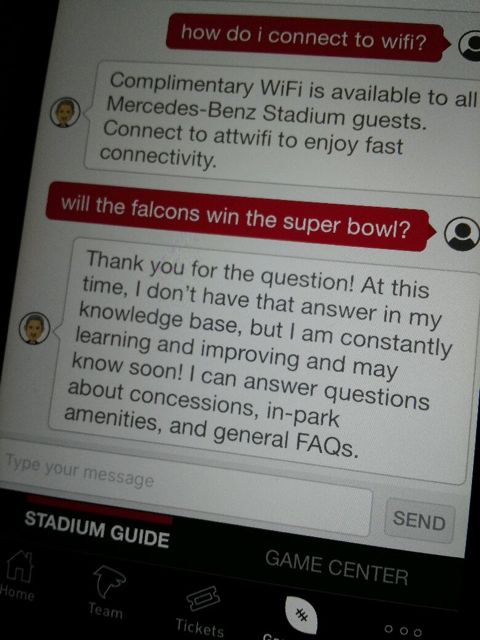

One experiment worth watching is the system being deployed by the Atlanta Falcons at Mercedes-Benz Stadium as part of the team/stadium app developed by IBM. Instead of working online, the app will let fans pick food items and enter payment information, and then take their phone to the appropriate stand to scan and fulfill the order. Nobody knows yet if this will speed up lines or make the concession process faster, but it is at the very least an attempt to try something new, using technology doing what it does best to eliminate a pain point of going to a game — waiting in line.

And while I will be excited to see the new networks being planned for Wrigley (Wi-Fi and a new DAS are supposed to be online for next season), I’m just as sure that whenever I visit there again, I won’t need an app to have a beer and hot dog brought to my seat. Maybe having more choice in items or having that instant gratification of delivery when you want it is where the world is going today, but on a brilliant summer afternoon at Wrigley Field somebody walking down the aisle every now and then works just fine. With the Cubs winning, the organ playing and the manual scoreboard doing its magic in center field, it’s a welcome reminder that sometimes, technology isn’t always the best or neccessary answer.