When will venues like Ohio State’s ‘Horseshoe’ be full of fans again? Credit all photos: Paul Kapustka, STR (click on any picture for a larger image)

To be sure, sports of all kinds are starting to test the waters on how they might return to action after the initial coronavirus shutdowns, and eventually how they might start welcoming fans back into their venues. But without any coherent top-down direction from the federal government, and what looks like an even bigger surge of new virus infections, the current state of how fans will return to venues in the U.S. is an uncoordinated chaos, with teams, leagues, schools, governments and fans all trying to find a way forward on their own that balances the need for safety with the desire to see live events in person.

After conducting a wide-ranging series of interviews with subject matter experts, industry thought leaders and representatives from teams, schools, leagues and venues earlier this year, Stadium Tech Report has come to some early conclusions about what the remainder of 2020 and beyond might look like for the world of professional and big-school sports. While all of these are still only best guesses as to what might happen, there are some trends that seem to be the way most operations will proceed as the search for a vaccine or some other type of coronavirus cure or treatment goes on.

1. Get ready for more events without any fans, maybe until next year.

Editor’s note: This profile is from our latest STADIUM TECH REPORT, which is available to read instantly online or as a free PDF download! Inside the issue is a look at a new Wi-Fi 6 network for Dodger Stadium, plus a profile of Globe Life Field! Start reading the issue now online or download a free copy!

In our research partnership with AmpThink (see Bill Anderson column) Stadium Tech Report agrees that the AmpThink-developed theory of a “stages of return” process is what we think most venues will need to go through in order to safely start allowing fans to attend events again. The first two parts of that process, getting government approval to open the doors to crowds and satisfying liability issues surrounding the safety of people in any building, are a combination that we see likely to push many venues into hosting events without fans – or in some cases, with severely restricted numbers of fans – since having only competitors and necessary staff, and perhaps a small number of fans inside the venues is likely an order of magnitude easier (and cheaper) to accomplish.

Granted, there are many sports and concert operations that may not have any incentive to hold events without fans, since their revenue models may lean heavily on game-day spending for food and beverage. However, the bigger sports with big TV deals would at least be able to earn some percentage of their incomes by holding empty-stadium events that would still be broadcast. Some sports, like NASCAR, bull riding and some independent minor-league baseball teams, have had limited-attendance events already. The PGA had proposed letting some fans in to the Memorial Tournament this week, but those plans were scrubbed in the face of the recent virus surges.

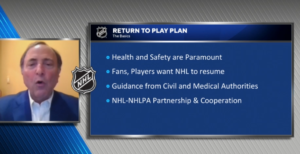

Right now the NBA and the MLS are in motion with plans to finish their seasons in a “bubble” type atmosphere in Orlando, where teams would be sequestered and would play at close-by facilities. The NHL and Major League Baseball are also in motion with plans for similar shortened seasons, with NHL teams playing in two cities in Canada (Edmonton and Toronto) while MLB teams will play 60 regular-season games in regional circuits.

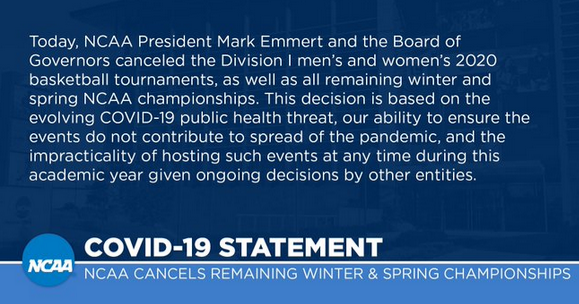

College sports, with larger rosters and no ability to enact a pro league-type “bubble,” may not see any sports this fall. Already, the Ivy League has canceled sports for the rest of the year while two Power 5 conferences, the Big Ten and the Pac-12, have eliminated non-conference games in order to provide more flexibility in scheduling. Even then, representatives in those conferences admit that the end result may be fully canceled seasons.

And in the NFL, teams are already publicly planning for reduced-capacity seating if games take place at all, and if so if they are allowed to have fans in the stands.

The key thing similar to all the ideas? Even with contract agreements in place, some of those plans still face huge hurdles when it comes to testing, quarantines and overall health concerns for both participants and guests, factors that may eventually end any or all of the experiments before seasons can be finished. There is also a new growing social concern over pro leagues having instant access to Covid-19 testing while the rest of the nation is starting to struggle again with getting tests and results.

A crowded concourse at Ohio Stadium in 2019. Venues will be challenged to keep fans apart during the pandemic.

No matter what the state or local governments decide, satisfying the combination of the second stage of the “return to venues” model – addressing the legal liability of the venues – and the third stage, which is gaining confidence of the fans – will likely push many venues to hold fan-free events first, while they work on plans and technology deployments to help get them to a place where they can earn government approval to open, to feel legally confident that they can keep fans safe, and then convince fans of that feeling.

While there will always likely be some fans willing to attend events no matter what the risk is, with national polls showing that a majority of people in the country are still in favor of restricting business activity to keep everyone safe from the virus, it might not make business sense for venues to try to open widely if big crowds don’t want to show up just yet. And events with less than full-house attendance may also not be economically feasible for many venues, given the large costs associated with just opening the doors of a stadium-sized facility; if you can’t make enough money to cover costs with a smaller audience, does it make sense to hold the event at all?

So just from a baseline measure of costs, safety and operational complexity, the feedback we’ve received from our interviews leads us to guess that most “big” events for the rest of the year will have no fans or strictly limited, small amounts of fans in attendance, if the events happen at all.

2. When fans do return to venues, new technologies and processes will be required, especially for venue entry and for concessions.

When it comes to social distancing to keep the virus from spreading, at large public venues it’s all about the lines.

With the prospect of an all-clear vaccine a year away at best, after some time the economic pressures of the current closures may become untenable if teams and venues want to survive as businesses. So, opening venues to some number of fans before a vaccine is available seems extremely likely; and in all discussions we’ve had so far, it’s apparent that venues believe they will need to enforce social distancing among guests, much like we are all doing in various phases of public activity today.

In seating areas, social distancing will be an easier task, given that venues can more easily keep seats unsold or erect barriers to keep unrelated groups apart from each other. The real problem with social distancing in stadiums comes from lines, a historical commonplace occurrence at entryways, on concourses and at places like concession stands and restrooms. To eliminate lines and to keep guests from inadvertently getting too close to one another, venues are likely going to need to deploy some kind of combination of technology and procedures to streamline the logjams we all used to just tolerate as part of the game-day experience.

Venues may require cashless transactions during the pandemic, like this stand at Atlanta’s Mercedes-Benz Stadium did in 2018.

Even in the face of all those barriers, many fans at big events still waited until near start time at tailgate parties or other outside-the-venue events, leading to large traffic jams of fans at the entry doors near the starting times. To allow fans to attend large events during a pandemic, however, fans may be asked to arrive even earlier to go through more thorough security checks that may include new procedures for temperature scans and perhaps even blood oxygen-level scanning; some venues may even choose to implement on-the-spot testing for Covid-19, new procedures that will likely force many venues to expand the geographic area needed to support all the new entry procedures.

New technologies, some of which have already been put in use in limited deployments, may offer some help in entryway procedures. The use of near-field communications (NFC) systems to allow personal devices to be scanned for valid tickets without having to present the devices could theoretically significantly speed up entry lines, with the caveat being that fans would have to adopt such payment or ticketing systems before arriving. Other venues are also looking at newer forms of threat-detection devices like metal detectors that can scan groups of people at a single pass instead of the airport-style one-person gate that is currently the de facto standard.

A no-tech additional solution being considered by other venues is the idea of reserved or staggered entry times, which could streamline the process if fans are able to or forced to comply. Similar methods have already been proposed for departure, with fans being instructed by section or row by row when it’s safe to leave.

The idea of entering at any gate and being able to wander around the entire stadium may also be something eliminated during a social-distancing audience phase. Some venues are considering highly regulated “zones” inside venues to keep fans apart. What is true of all plans, technology-aided or not, is that any new measures will require huge amounts of communication outreach to fans, a large amount of training and even new staffing for stadium workforces, and a new level of compliance, regulation and policing, all extra-cost measures during a time of significantly reduced revenues.

The contact-free concessions experience

Over the past year or so, many large public venues have already tested or had small deployments of so- called “contact-free” concessions technologies, where fans could order and pay for concessions via their mobile device, then either picking up orders at a specified window or having orders delivered to their seats. Other stadiums have already experimented with various forms of “grab and go” concessions stands, where pre-made items are offered for fans to take, with some deployments also featuring self-scan payment options.

The general idea of having fewer or no human interactions at all for concessions transactions will likely be the most widespread technology and process change for venues opening up during the pandemic. For most of the venue representatives we spoke to, plans that were already in place for some move to contact-free concessions operations will likely just be accelerated since such deployments will probably remain popular even after concerns about virus transmissions subside.

Grab-and-go concession stands, like this one at Denver’s Empower Field at Mile High in 2019, may be more prevalent in the near future.

One area of food service where there isn’t much consensus yet on what is to come is the area of club and other premium spaces, which in the past few years have mainly trended toward buffet-style offerings, sometimes as part of an all-inclusive cost system. While safety concerns have some observers predicting an early demise for the large-venue buffet, others see possibilities of having more closely staffed buffet operations, like the cafeterias of the past where a server (most likely behind a glass shield) can prepare individual plates. Premium suite services are also seen as an area heading for massive changes, with more prepackaged food and beverage options likely instead of the traditional steam-tray or open-serve catered offerings previously found in most venues.

3. Critical networks will be needed to support everything new and old

If there ever really was a question about whether or not wireless networks were needed inside venues, the advent of the coronavirus pandemic has removed all doubt. According to several sources we’ve talked to, some networking deployments or upgrade plans that had been “on the fence” prior to the outbreak have now been quickly green-lighted, as venues everywhere realize that critical networks will be even more important going forward, as new technologies and new procedures demand increased levels of connectivity.

On the technology side, it is clear that if venues are looking to add new layers of devices like sensors and threat detectors, there is going to be a need for greater wireless connectivity, sometimes in new areas of the venue that may not have previously had a priority for bandwidth. Entry areas in particular, and perhaps also spaces just outside venues, will likely need more carrier-class connectivity going forward, as venues seek to automate more transactions like ticket-taking and parking payments.

Installation of more mobile concessions technology, like kiosks and even vending machines, will also increase the need for overall connectivity, as will a shift to more fans using mobile devices for concessions ordering and payments as described previously. Venues are also likely going to want to increase the amount of digital displays in their buildings, to assist with crowd control, wayfinding and social-distancing policing – again leading to more demand for both wired and wireless connectivity.

Layer in more increases in communication demands just from a fan-education standpoint as well as any growth in demand for public safety and other operational needs and it’s clear that providing or upgrading existing networks to a much more robust state is probably the first to-do item on many venues’ work lists as they seek to support the return to venues. The good news is, from a technology and market perspective, there may not be a better time to be seeking new horsepower and capacity on a wireless-networking front.

On the Wi-Fi side, the advent of Wi-Fi 6 networking gear – now available from most top vendors – should provide a large boost in performance and capacity for venue networks, at costs only slightly higher than the past generation of equipment.

On the cellular side, 4G DAS networks remain a key tool in bringing a multi-carrier solution to providing basic access to most devices, while the arrival of nascent 5G services will enable carriers and venues to bring new kinds of services to guests, including applications with low-latency needs like virtual reality and other high- bandwidth broadcasts. Also, the emergence of networks using the CBRS bandwidth for potential “private” LTE networks may provide venues with an additional method of adding secure, standards-based communications for things like back-of-house operations, in-venue gaming, and Wi-Fi like services or Wi-Fi backhaul to areas where Wi-Fi signals can’t reach.

While budgetary concerns, venue aesthetics and demand for levels of services will still likely make overall networking choices a very local decision, the idea of trying to move forward in a pandemic age without a high level of basic wireless connectivity seems to be a non-starter.

A situation that changes day to day

As we said at the start — right now, the only thing everyone knows for sure is that nobody knows anything for sure. From our interviews, however, it is very apparent that for almost all the people we have talked to, few see standing still as a viable alternative. There are almost assuredly going to be some missteps, some money and time spent on technologies or procedures that don’t pan out, some anger and frustration on all sides, as we all adjust to new ways of doing things we’d long taken for granted. There will also be successful moves, victories small and big, which we hope to share to help accelerate the “Return to Venues” as much as possible.

Here at Stadium Tech Report, nothing has changed in our core directive — trying to help bring the best information possible to our readers so that they can be successful in operating their venues.